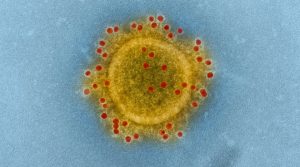

The Canadian medical system coped well COVID-19. The imminent threat of illness and possible death got a lot of people thinking about their wills, and also about powers of attorney.

In Ontario there are two powers of attorney, one for property and one for personal care. The personal care power deals with your person, your health and care.

An Advance Care Directive is not a power of attorney, but related. It is a document that sets out how much or little medical treatment you want to have if you are very seriously ill and close to death.

Everyone should have one of these, especially if you are older or vulnerable health-wise. There’s no better time than the present to “get your paperwork in order“, i.e. take care of something you want to have taken care of.

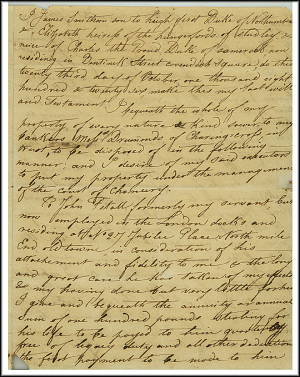

First of all, you will need a Power of Attorney for Personal Care, a document that gives someone close to you, a family member or friend, the authority to make decisions for you if you cannot do it yourself. This is an important document if you become unconscious or are too medicated to be able to make good decisions and give instructions to your doctor. Your “attorney”, the person given authority by the document, is empowered to make decisions on your behalf.

But what decisions are they supposed to make? Do they decide on the basis of what they think is best for you? Or do they guess what you might want for yourself? How are they to know what you would want in the way of treatment?

The Advance Care Directive takes the guess work away; you complete a form that tells your attorney what you would want in the way of medical intervention, for example, if you have untreatable illness that is terminal or causes unbearable pain.

So it is a good idea to have both the Power of Attorney for Personal Care and the Advance Care Directive. They go together. Give copies to your attorney, or better yet, have the conversation with them before hand about your wishes.

No one wants to make a decision to end their life in advance of facing actual life-threatening illness. But should you come to a point where a decision like that is needed, wouldn’t it be better to have given it some thought before hand and to be prepared?

The non-profit organization Dying with Dignity thinks so, and has prepared a very complete kit that explains the decision-making process and includes the needed forms. Get the right kit for your province here. They want you to know that making decisions about your health is always a matter of right:

Knowledge is Power: Know Your Rights:

The right to be fully informed of all treatment options. This is also known as the right of informed consent. Your healthcare practitioner is required to inform you of the risks and benefits of each treatment option as well as the probabilities of success.

The right to recognition of a substitute decision-maker. You have the right to appoint a substitute decision-maker (SDM), someone who can represent you when you can no longer make your own medical decisions. Your SDM can speak for you with the same authority as if you were speaking for yourself.

The right to recognition of an advance care plan. Regulations vary by province or territory, but in general, healthcare providers are required to follow your wishes for treatment, provided they are appropriate to your medical condition and are clearly outlined in a valid advance care plan. Your substitute decision-maker must make the decisions you would make for yourself if you were able; this usually requires following your advance care plan.

Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) forms are legally binding in provinces or territories that offer them, so long as the documentation is filled out properly and up to date.

The last document listed above could be a crucial one in the COVID-19 crisis: the DNRCF (Do Not Resuscitate Confirmation Form) or what is known in popular parlance as a DNR (Do Not Resuscitate). It is where you can officially declare that you want less rather than more treatment. It is a legal form that would, in the context of COVID-19, allow health care professionals to care for others who may have a better chance of recovery. This powerful form can only be obtained from hospitals and must be signed by a doctor. Once signed, paramedics and other health care providers are legally bound to not provide extreme measures such as CPR or intubation to revive someone, but instead must allow natural death to occur.

The last document listed above could be a crucial one in the COVID-19 crisis: the DNRCF (Do Not Resuscitate Confirmation Form) or what is known in popular parlance as a DNR (Do Not Resuscitate). It is where you can officially declare that you want less rather than more treatment. It is a legal form that would, in the context of COVID-19, allow health care professionals to care for others who may have a better chance of recovery. This powerful form can only be obtained from hospitals and must be signed by a doctor. Once signed, paramedics and other health care providers are legally bound to not provide extreme measures such as CPR or intubation to revive someone, but instead must allow natural death to occur.

Through the COVIC crisis, we learned that intubation is often required at the last desperate stages of the disease and few people recover from that stage even if intubated. It is often already too late, yet ethically hospitals and doctors are committed to using all resources, staff and equipment that they can to keep a patient alive.

P.S. April 16th is National Advance Care Planning Day in Canada